Little Island, Major Expense: The Ethical Considerations of Public-Private Partnerships

By Zikora Akanegbu

I. Introduction

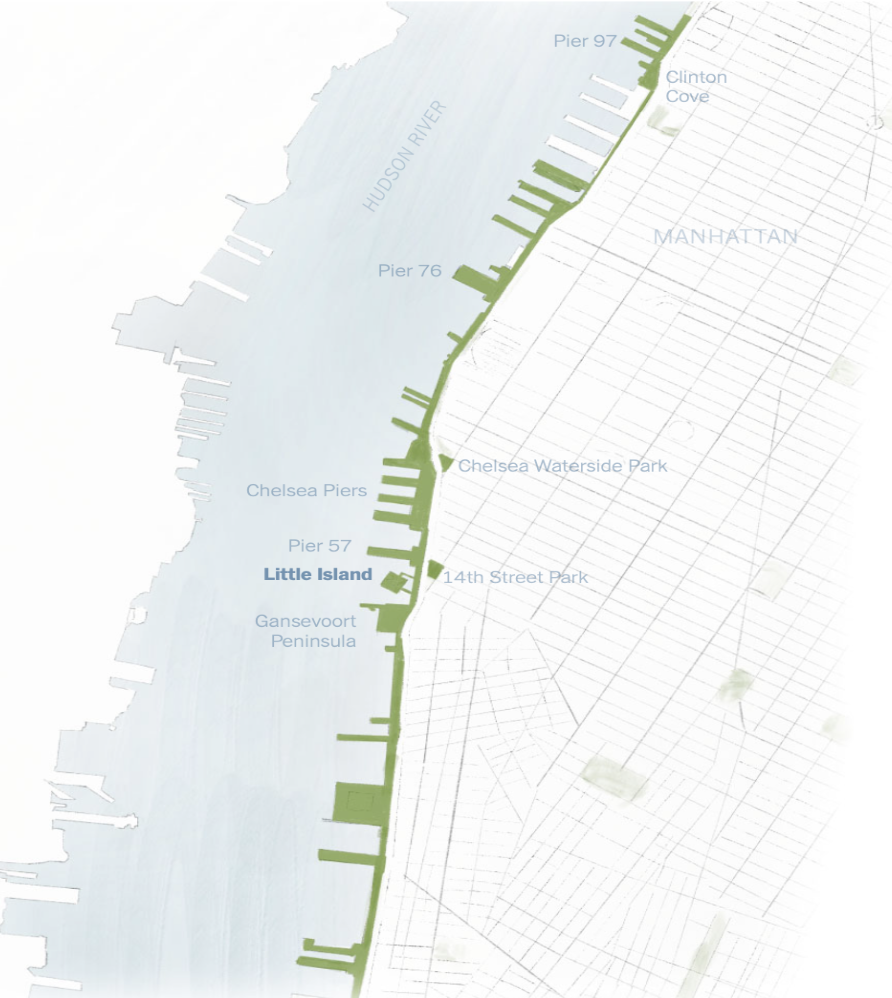

In the midst of the darkness of the COVID-19 pandemic in New York City, a bright ray of optimism arrived on the site of Pier 55: Little Island. The man-made park is suspended above the Hudson River, the river that separates Manhattan from New Jersey. It sits on the edge of Chelsea’s Pier 51, a formerly working-class neighborhood that has become among the wealthiest neighborhoods in Manhattan (Plitt, 2019). The area that Little Island is located in was already a tourist hotspot due to the High Line being located nearby, an elevated railroad track that transformed into a public park in 2009 (Friedrich, 2021). In addition, the Hudson River Park was formed in 1998 when local donors and officials decided to transform the waterfront (Foderaro, 2015). According to Google Maps, Little Island is a five minute walk from The High Line and a thirteen minute walk from The Hudson River Park. Furthermore, the premise of Little Island being located in a luxury, affluent part of Manhattan creates a sense of exclusion. Arguably, building another green space in an area that already contains The High Line and Hudson River Park was not a wise location choice. While Little Island encourages local residents and tourists to escape the busy city and experience both nature and art, it ultimately is a public space that does not truly serve an unmet need for the area it is based in.

Figure 1. The photo by Timothy Schenck (2021) shows how Little Island is a floating park on the Hudson River.

Figure 2. The map by Scott Reinhard (2021) displays the current Hudson River Park sites. Little Island is located off 13th Street on the West Side of Manhattan.

II. A Brief History of the Development of Little Island

Hurricane Sandy struck the New York City shore in October 2012, damaging much of the already brittle nearby Pier 54 and several other piers along the Hudson River (CBS Sunday Morning, 2021, 2:45-3:02). In November 2014, Barry Diller, a media mogul, and his wife, Diane von Furstenberg, in partnership with the Hudson River Park Trust announced a plan to replace the terribly deteriorated Pier 54 into a high-concept public park that would be centered on Pier 55 and replace Pier 54 altogether (Hudson River Park).

III. The Long Dispute Over Little Island

Douglas Durst, a real estate developer, was annoyed that the Hudson River Park Trust allowed a billionaire to decide what is built on public land. Durst bankrolled a series of lawsuits filed by the non-profit City Club of New York. Adversaries sued and battled in court to stop Little Island; they expressed how the creation of Little Island was done in secrecy and that the park had been planned without input from the public because it was intended for the affluent (The New York Times Editorial Board, 2017). In addition, some environmental organizations expressed that Little Island could potentially impact the ecosystem of the Hudson River by increasing water pollution and disrupting fish habitats (Kothari 2022). In 2017, Diller decided to pull the funding for Little Island after seeing no end in sight to the court fights. However, Andrew Cuomo, the Governor of New York at the time, stepped in and saved the project by brokering a deal (Kimmelman, 2021). Diller agreed to revive the project. In 2019, the name of the project changed to reflect its design: Little Island. Previously, its name was Pier 55 (Robbins, 2019). The public park officially opened to the public on May 21, 2021 (Little Island).

IV. Little Island: A Futuristic Floating Park

The $260 million project was primarily privately funded by the Diller Von Furstenberg Family Foundation which was the largest donation to a public park in New York City history (Rooney, 2014). The couple pledged to donate an additional 120 million dollars for maintenance and programming costs for the next twenty years (CBS News, 2021). Also, Little Island was partially financed using public funds. Governor Andrew Cuomo and Mayor Bill de Blasio continually pushed for the development of the park. New York City contributed seventeen million dollars to the project and New York State contributed four million dollars, respectively (WestView News, 2021). However, addressing the real problems the city and its residents are facing should be the first priority when it comes to funding large budget projects.

Figure 3. The photo by Amr Alfiky (2021) shows how Little Island is supported by dozens of pot shaped structures referred to as ‘tulips’ that vary in height, rising out of the water (Green, 2021).

Figure 4. The photo by Timothy Schenck (2021) displays the pot shaped structures up-close.

Figure 5. The photo by Timothy Schenck (2021) displays the greenery that surrounds Little Island.

Figure 6. The map, from Little Island’s website, breaks down the park into different sections to provide a sense of what Little Island looks like from a map view perspective.

V. Little Island Offers Locals and Visitors an Oasis of Nature and Art

At Little Island, people can walk along the pathways of the park amidst the greenery and view a wide-array of awe-inspiring public art displays. In the book, “The Granite Garden: Urban Nature and Human Design,” Anne Whiston Spirn paints the city and nature as one spectrum with the ends of the scale being urban development and nature which are often pitted against each other. Spirn states, “The city must be recognized as part of nature and designed accordingly. The city, the suburbs, and the countryside must be viewed as a single, evolving system within nature, as must every individual park and building within that larger whole” (Spirn p. 5, 1984).

Figure 7. The photo by Mike Segar (2021) shows people sitting back and relaxing on the Main Lawn.

Although urban environments may make humans feel disconnected from nature, Little Island was thoughtfully designed in tandem with nature. Additionally, the park offers programming for all ages which includes the following: dance, thetater, music, comedy, art, and poetry. Little Island also has an open air, wooden-benched amphitheater (known as “The Amph'') which serves as the main performing area for music performances and plays; it seats up to 687 people. A smaller, more intimate stage and lawn space in an area called the Glade hosts additional performances (Hudson River Park).

Figure 8. The photo by Timothy Schenck (2021) shows Little Island’s amphitheater.

Figure 9. The photo, from Little Island’s website, displays a variety of different activities that people can do while visiting Little Island.

VI. Conclusion

Little Island is a public space that was wished into existence by a billionaire. Mack Travis, an experienced real estate developer, states the following in his book Shaping A City: “Most real estate transactions take place behind the scenes. The public is never even aware of them until they are announced” (Travis p. 103, 2018). This scenario proved to be correct for the case of Little Island. The designers gave the donor what he wanted by responding to the needs of the few over the many. The best gifts are not about the donor, but rather they are about the recipient which often entails asking them what they want. Looking to the future, large-scale nature based projects in cities will be partly driven by private investors who intend to attract well-to-do visitors to the areas that they help develop. However, to include biophilic design into urban life there are more cost-effective ways than large-scale green projects. In an interview, Diller states, "We're lucky. We've got resources, so we could build something that was unexpected. Do we have the right to? No, but in fact, this was a torn-down pier in which nothing but a flat space was gonna replace it” (CBS Sunday Morning, 2021, 4:12-4:31).

Little Island is more of a tourist attraction than an actual park. In fact, Little Island attracts more than seventeen million visitors each year. Importantly, the Hudson River Park attracts seventeen million visitors yearly (Hudson River Park) and the High Line attracts eight million visitors yearly (Matthews, 2019). Clearly, the public spaces nearby Little Island have also attracted a lot of attention. Furthermore, the creation of Little Island came at the grave expense of some local residents who are not thriving. New York City did not need a whimsical park. The money could have instead been donated to the city to improve public transportation or fund crime prevention projects and underfunded public libraries and schools. Additionally, the money instead could have been used to fund affordable housing programs since New York City is home to the second highest population of homelessness in the United States. Barry Diller built a tiny park in an already affluent neighborhood when he instead could have found a better use of his money by contributing to resolving pressing issues. Ultimately, while Little Island may be Diller’s ideal park, it does not line up with the expectations or needs of local residents.

SOURCES

Foderaro, Lisa W. “How Diller and von Furstenberg Got Their Island in Hudson River Park.” The New York Times, 5 April 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/05/nyregion/how-diller-and-von-furstenberg-got-their-island-in-hudson-river-park.html. Accessed 1 December 2023.

Friedrich, Michael. “Escape From Little Island.” The Baffler, 10 June 2021, https://thebaffler.com/latest/escape-from-little-island-friedrich. Accessed 1 December 2023.

Green, Jackie Wei. “Little Island Opens Today Unlocking Over Two Acres of Public Park and Performance Space Above the Hudson River.” Arup, 21 May 2021. https://www.arup.com/news-and-events/little-island-park-opens-in-new-york-city. Accessed 1 December 2023.

Kimmelman, Michael. “A New $260 Million Park Floats on the Hudson. It’s a Charmer.” The New York Times, 20 May 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/20/arts/little-island-barry-diller.html. Accessed 17 November 2023.

Little Island, 2021, https://littleisland.org/explore-the-landscape/. Accessed 16 November, 2023.

“Little Island – Hudson River Park.” Hudson River Park, https://hudsonriverpark.org/locations/pier-55-little-island/. Accessed 17 November 2023.

Margolies, Jane. “How Hudson River Park Helped Revitalize Manhattan’s West Side.” The New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/09/19/business/hudson-river-park-development-manhattan.html. Accessed 1 December 2023.

Matthews, Karen. “NYC’s High Line Park Marks 10 Years of Transformation.” NBC New York, 9 June 2019, https://www.nbcnewyork.com/news/local/nycs-high-line-park-marks-10-years-of-transformation/1646268/. Accessed 9 December 2023.

“New York City’s Little Island.” YouTube, uploaded by CBS Sunday Morning, 25 June 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RZ6kxYxyvI4. Accessed 16 November 2023.

“New York’s Newest Island, A Man-Made Gift to the City,” CBS News, 25 July 2021, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/little-island-new-york-city-hudson-river/. Accessed 1 December 2023.

“NYC’s Little Island at Pier 55 Is Now Open Along the Hudson River.” New York Family, 21 May 2021, https://www.newyorkfamily.com/little-island-at-pier-55-new-york/. Accessed 1 December 2023.

Pintos, Paula. “Heatherwick Studio, MNLA and Arup on their Collaborative Design for New York's Little Island Park.” ArchDaily, 15 December 2021, https://www.archdaily.com/973517/heatherwick-studio-mnla-and-arup-on-their-collaborative-design-for-new-yorks-little-island-park. Accessed 1 December 2023.

Plitt, Amy. “The Richest Neighborhoods in New York City.” Curbed New York, 27 December 2019, https://ny.curbed.com/2017/6/27/15881706/nyc-richest-neighborhoods-manhattan-brooklyn. Accessed 9 December 2023.

Kothari, Khusi.“Project in-depth: Little Island at Pier 55, New York,” Rethinking The Future, 2022, https://www.re-thinkingthefuture.com/case-studies/a9635-project-in-depth-little-island-at-pier-55-new-york/. Accessed 10 December 2023.

Robbins, Christopher. “Diller Island Shall Henceforth Be Known As 'Little Island,' An 'Oasis Of Everything Fun.'” Gothamist, 13 November 2019, https://gothamist.com/news/diller-island-shall-henceforth-be-known-little-island-oasis-everything-fun. Accessed 1 December 2023.

Rooney, Ben. “Billionaire Diller’s $130 Million New York City Floating Park.” CNN, 27 November 2019, https://money.cnn.com/2014/11/17/news/barry-diller-nyc-park/#:~:text=The%20%24130%20million%20project%20is,in%20New%20York%20City%27s%20history. Accessed 9 December 2023.

Spirn, Anne Whiston. The Granite Garden: Urban Nature and Human Design. Basic Books, 1984.

“Then & Now: Pier 54, 55, and Little Island.” WestView News, 2 July 2021, http://westviewnews.org/2021/07/02/thennow-pier-54-55-and-little-island/gcapsis/. Accessed 1 December 2023.

The New York Times Editorial Board, “How New Yorkers Sank a Floating Park.” The New York Times, 15 September 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/15/opinion/pier55-diller-floating-park.html. Accessed 1 December 2023.

“Transforming Hudson River’s Pier 55 Into a Whimsical Urban Park and Performance Venue.” Arup, https://www.arup.com/projects/little-island. Accessed 17 November 2023.

Travis, Mack. Shaping a City: Ithaca, New York, a Developer's Perspective. Ithaca, NY, Cornell University Press, 2018.